For the mining sector, the NAB Monthly Business Survey for May 2016 presents some familiar findings. Economic recovery in the sector remains weak, and confidence is lower than in all other industries at -5. There is a silver lining – NAB estimates that the mining investment downturn is halfway through.

A revitalisation of the industry could be in the cards earlier than expected – one that focuses not on how minerals are removed from the ground, but on which minerals are mined.

A shift away from hematite in Pilbara?

The Pilbara’s red appearance is an indication of its mineral wealth – the vast stores of red hematite iron ore that lie underground. The quality of that hematite, however, has been on a downhill slope for some time. According to Asia Iron Limited, the iron content of hematite in the Pilbara has dropped by 2 per cent in the ten-year period from 1998 to 2008. The trend, however, is much more pronounced over time.

Is it time for the Pilbara to shift from hematite to magnetite mining?

“The head grade of the ore is coming down. In the 1970s, it was in the high 60 per cent range. Now, it is in the high 50 per cent range – and the impurities are increasing,” said Chen Zeng – CITIC Pacific Mining CEO – in an interview with Australia’s Mining Monthly.

Zeng believes that this drop in quality is an indicator that the time has come to consider ditching hematite iron ore in favour of magnetite.

“If Western Australia wants to keep and maximise its competitiveness, [it] needs magnetite mines,” he said.

Why mine magnetite?

There’s a reason hematite has been the preference for so long – it is easier and more cost-effective to mine. With a simple beneficiation process – crushing, screening and blending – getting steel from hematite ore is more streamlined than magnetite. In contrast, magnetite must be thoroughly processed to extract enough quantities of the usable mineral.

Hematite may be common in the Pilbara, but its quality has been on the decline for some time.

Hematite may be common in the Pilbara, but its quality has been on the decline for some time.Mined magnetite ore only contains 25 to 40 per cent iron, according to the Magnetite Network. Once refined, however, that jumps up to 68 to 70 per cent iron – much to the appreciation of steel manufacturers.

Chen Zeng believes that this, along with magnetite’s consistency and lower pollutant risk, spells out a bright future for magnetite in the Pilbara, especially as pollution is becoming a key area of concern in China.

This should be a major enticement for pursuing magnetite, given that much of the iron ore exported from the Pilbara makes its way to Chinese markets. According to the Pilbara Ports Authority, over 31.6 million tonnes of iron ore were exported to China in May 2016 alone – the largest recipient of Pilbara iron ore by a significant margin.

Overcoming magnetite challenges

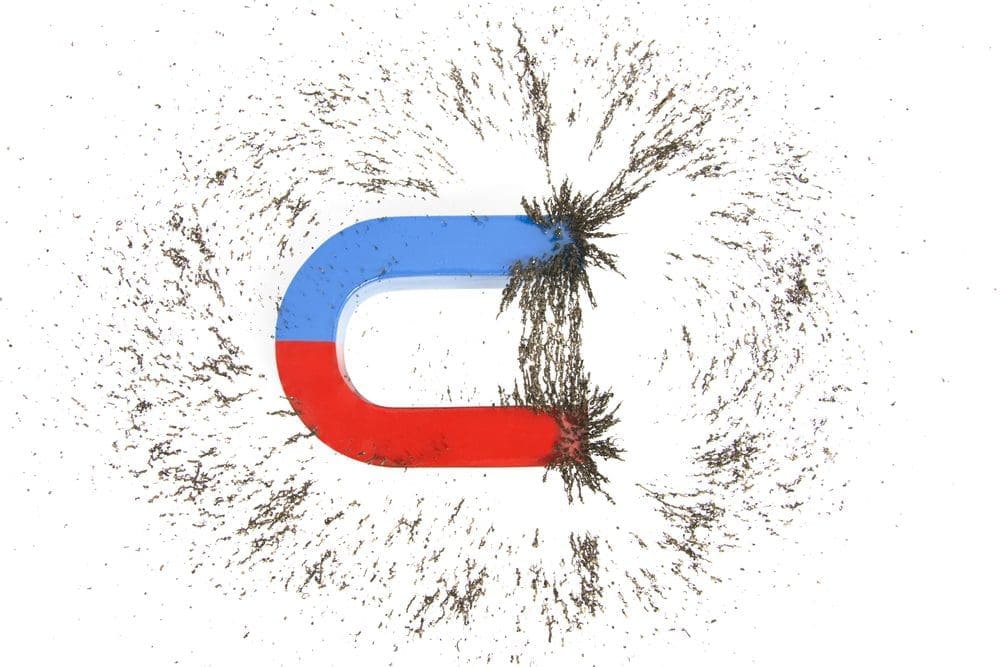

Magnetite can cause issues during material movement, particularly with conveyor belts.

Switching from hematite to magnetite mining, however, is not a simple task. There are a number of issues that must be worked out before mining magnetite ore becomes the most feasible option. In addition to the more involved beneficiation process, magnetite can cause issues during material movement, particularly with conveyor belts.

Unlike hematite, magnetite is – as the name would suggest – magnetic. Over time, this can cause splice connections on steel cord conveyor belts to also become magnetised. When that happens, it can interfere with the performance of tramp metal detectors. This can lead to costly production delays, as operations must be halted to identify these errors.

Recent Comments